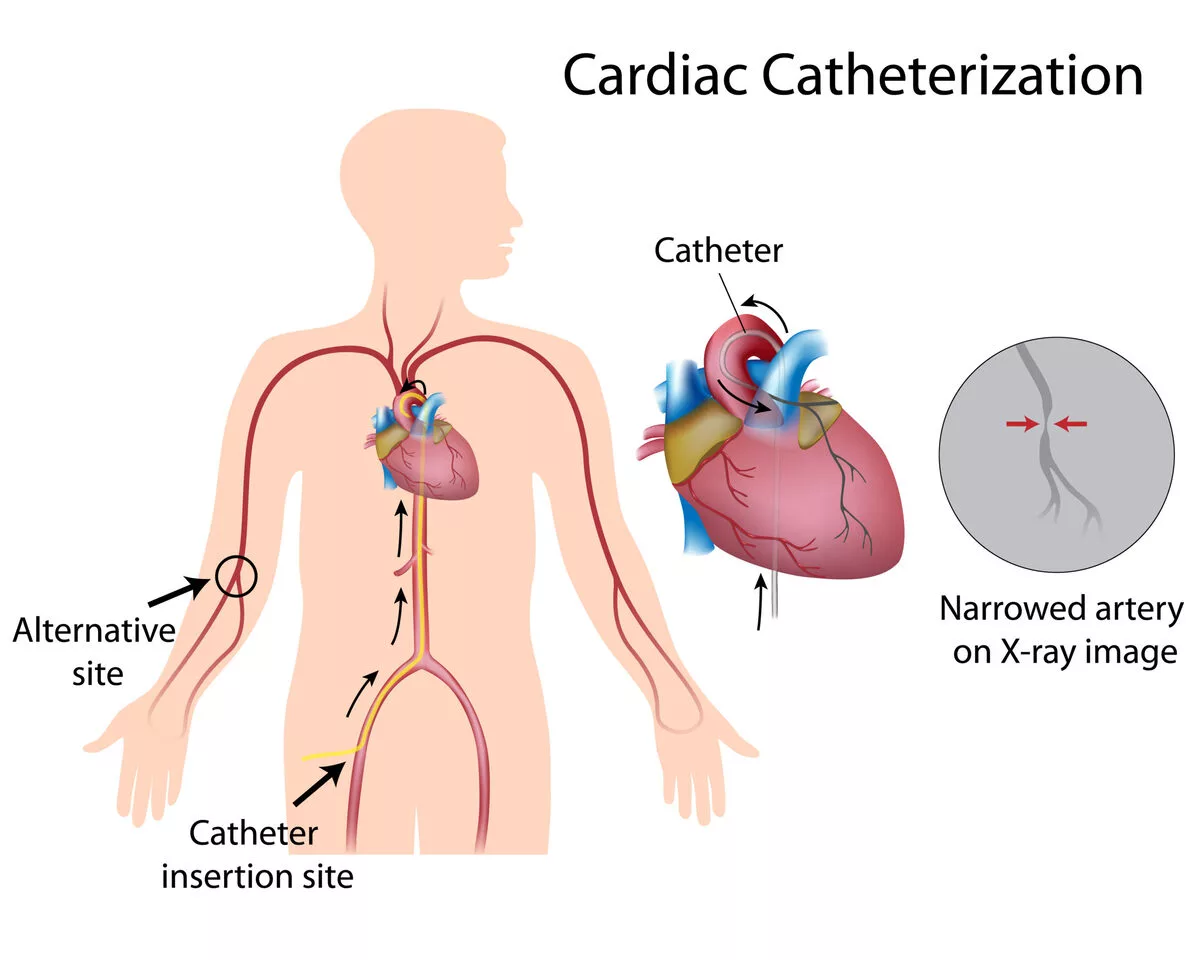

Having recently undergone cardiac catheterization, a catheter was inserted either through an artery located in your groin or arm. Post-procedure, you might have noticed bleeding at the insertion site, potentially indicating a groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization. The bleeding might either drool or spurt out or accumulate within a lump (hematoma) beneath the skin.

This necessitates an immediate emergency room visit. While waiting for medical help, apply direct pressure on the affected area, and, if possible, get someone to escort you to the emergency department. At the hospital, experts will apply additional pressure on the wound to curtail bleeding. Discharge happens after the bleeding has halted. Yet, to prevent re-bleeding, some precautionary measures need adherence at home. If bleeding reignites, act as per the following recommendations.

Home Care Instructions

Over the next 48 hours:

- Avoid engaging in rigorous activities.

- Opt for level surfaces over stairs, if possible.

- Refrain from lifting objects heavier than 10 pounds.

- If the catheterization involved puncturing your arm or wrist, abstain from laying down on the affected side.

- In case the groin was the puncture site for cardiac catheterization, avoid exerting pressure during bowel movements to prevent the risk of a groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization.

- When bathing, avoid vigorous rubbing at the puncture site. Once your healthcare provider gives the green light, you can wet the area. But, be sure to avoid scrubbing or massaging it.

More about groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization

Objective: A groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization, also known as a retroperitoneal hematoma, is a rare yet potentially severe complication. This presentation outlines the specific predisposing factors, standard feature set, and clinical pathway of this post-procedure complication, as well as defines the role of surgical procedures in its management.

Methodology: A comprehensive retrospective examination of 9585 cases of femoral artery catheterizations over a half-decade enabled the identification and assessment of all patients who experienced retroperitoneal bleeding.

Findings: Out of the total number of cases, groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization emerged in 45 patients (equaling an overall rate of 0.5%), with the most occurrences following coronary artery stenting (at a rate of 3%). In patients who underwent this specific stenting, statistically substantial predictors of such complication encompassed the protocol for sheath removal, femininity, lowest platelet count, and over-coagulation.

Indicators and symptoms consisted of suprainguinal tenderness and fullness universally, accompanied by intense back and lower quadrant pain in 64% of the cases, and femoral neuropathy in 36%. A vast majority of the patients were treated effectively with blood transfusion only. However, seven patients (16%) required surgical intervention; out of these, in four cases, early post-catheterization hypotension unresponsive to volume restoration occurred, and in three cases, a continual drop in hematocrit level resulted in surgery 24 to 72 hours post-catheterization.

Decision-making concerning management can be challenging. Given the fact most patients have co-existing cardiac conditions, a retroperitoneal operation could add considerable morbidity. The exact treatment protocol for patients dealing with a groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization—specifically in the form of a retroperitoneal hematoma—still lacks clear definition. To pave a clearer path towards understanding this medical situation, we’ve conducted an assessment retrospectively of all patients at our institution who developed a retroperitoneal hematoma after cardiac catheterization over the previous five years.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

During a five-year span from July 1988 to July 1993 at Beth Israel Hospital, a total of 9284 cardiac catheterizations were conducted. We focused on patients diagnosed with a retroperitoneal, or groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization. This diagnosis was initially made based on physical examination and subsequently confirmed through computed tomography (CT) scans as needed. We identified these patients by perusing the cardiology registry and logs maintained by vascular surgeons J.J.S. and K.C.K., who were routinely consulted to address this complication.

Information was gathered from hospital records and the clinical computing database. Details about the type of catheterization procedure, patient demographics such as history of hypertension and sheath size, degree of anticoagulation, baseline and follow-up laboratory data were collected and analyzed. The data primarily came from a subgroup of patients enduring coronary artery stenting. In this group, we used univariate logistic regression to identify factors contributing to the risk of groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization. We then pinpointed independent predictors using the multivariate logistic regression model.

RESULTS

Across the study duration, 45 patients experienced a groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization, underlying a prevalence of 0.47%. An average patient age of 64 was noted among these patients, compared to the overall cohort average of 58. The gender split among patients experiencing a hematoma highlighted 60% being women (27 individuals), quite contrastive to the entire patient population where females represented only 27% of the cases.

Physical examinations shed light on suprainguinal tenderness, along with fullness, consistent across all patients. These conditions were usually accompanied by a dip in hemocrit levels not owing to any other hemorrhage source. Of these patients, 30 underwent CT scans, with each confirming a groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization. Many reported significant back or flank pain, with 64% requiring narcotics for relief. Femoral neuropathy surfaced in 36% of patients. An approximated blood loss of 4.6 units was observed, with the median transfusion amount being 4.0 units.

Only four patients didn’t receive a full course of heparin beyond the initial procedure. Of patients experiencing a hematoma, 24% were administered thrombolytic drugs, 27% received dextran treatment, and all were prescribed aspirin. Among these patients, 30% had initially arrived at the cardiology service harboring a myocardial infarction. This affirmed that these patients already faced severe health complications before the development of a groin hematoma post cardiac catheterization.

Groin Hematoma Incidences in Different Catheterizations: A Statistical Insight

Groin hematoma prevalence differed by catheterization type. Highest occurrence of 3% was associated with placement of a coronary artery stent. This was followed by percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (0.81%), diagnostic catheterization (0.17%), and coronary atherectomy (0%). All these deviations in prevalence rates were statistically significant, indicating a p-value of less than 0.05.

We further evaluated potential risk factors for retroperitoneal bleeding among a subset of 376 patients treated with coronary artery stents. These patients were administered a comprehensive course of anticoagulant following the procedure. We made two formal adjustments in the protocol, managing anticoagulation during femoral artery sheath removal, during this research. Factors affecting the development of groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization emerged in our univariate analysis. These include female sex, nadir platelet count, prolonged partial thromboplastin time (PTT) exceeding 100 seconds, and sheath removal procedure. A multivariate analysis led to nadir platelet count, female sex, and sheath removal protocol being recognized as independent predictors of retroperitoneal bleeding.

Conclusion about Groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization

Groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization – retroperitoneal hematoma, to be precise – is generally manageable through standalone blood transfusion. Nonetheless, a minor cohort of patients who develop volume resuscitation-resistant hypotension necessitate immediate surgical treatment. (J VASC SURG 1994;20:905-13.)

With the continual rise in the quantity and intricacy of diagnostic and therapeutic cardiac catheterizations, consequently, there is a proportional increase in complications arising from femoral artery puncture.

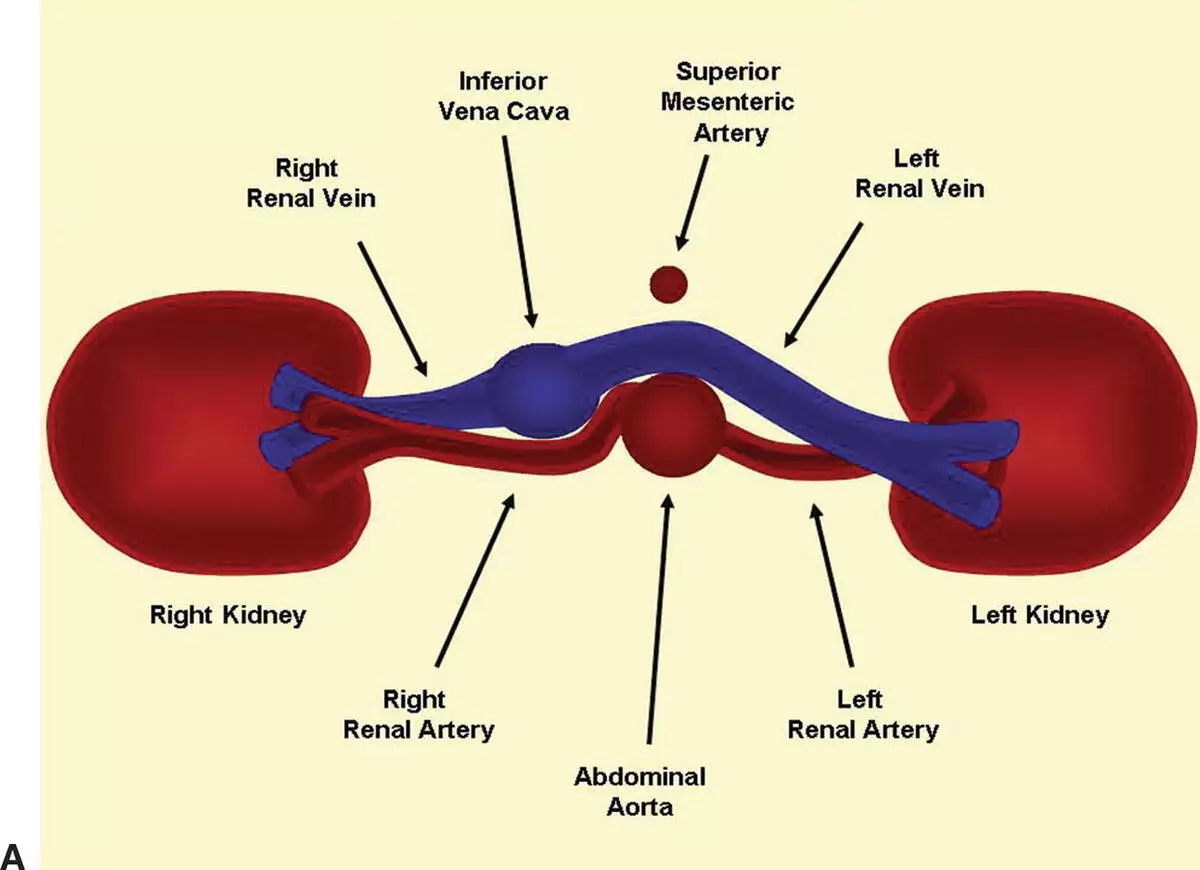

Most commonly, these complications—like false aneurysms, hematoma, arteriovenous fistula, or femoral artery occlusion—remain tied to the femoral artery and groin, often leading to a groin hematoma after cardiac catheterization. However, the incidence of retroperitoneal hematomas has been escalating. These hematomas are theorized to stem from unintentional punctures of the distal external iliac artery. The clinical range extends from a benign, limited condition necessitating only transfusion, to one presenting with uncontrolled bleeding and hypotension requiring immediate surgery.

Read more: Ecg leads coronary arteries